I was always fascinated by my grandfather's article remembering hog butchering on his aunt and uncle's farm. Being a child of the 1950s suburbs and the wide aisles of modern grocery stores, it was hard for me to believe that a little boy was witness to such a bloody and gruesome scene, none the less participating in the event. It makes me glad I am a vegetarian!

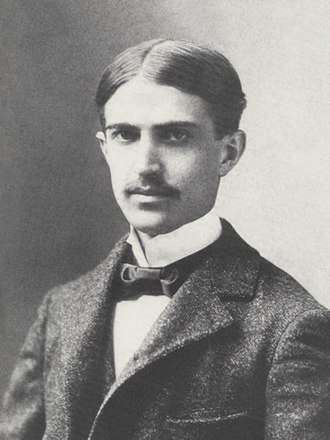

|

| Lynne at Six Years |

In 1960 my grandfather Lynne O. Ramer (1903-1971) wrote a series of articles for the Lewistown Sentinel, the local paper for his hometown of Milroy, PA. Gramps wrote close to 200 articles that were published in the Sentinel and other newspapers, many recounting tales of farm life in the early 20th c.

Gramps was orphaned before he was nine. After the death of his grandmother "Nammie" (Rachel Barbara Reed Ramer, second wife of Joseph Sylvester Ramer) he lived with his Uncle Charles and Aunt Annie Ramer Smithers or Uncle Ed and Aunt Carrie Ramer Bobb.

|

| Lynne with his cousin |

Gramps was very smart and in the 1920s went to

Susquehanna University and was ordained in the Evangelical Lutheran church. He took teacher's training at Columbia University along with his friend and fellow Susquehanna U alumni

Roger Blough who would go on to become president of U.S. Steel company.

Gramps taught at

Hartwick Seminary in New York State where he met my grandmother, and they moved to Kane, PA where he taught in the high school. My mom was born there.

|

| Lynne in 1952 at work |

During WWII Gramps was an engineer in the Chevrolet aviation factory in Tonawanda, NY and in his 'spare time' earned his Masters in Mathematics from the University of Buffalo. At this time he was ordained a deacon in the Episcopal church.

Around 1960 he moved to Michigan and taught Calculus and Trig at

Lawrence Technological University while still working for Chevy.

He became very interested in

research conducted by Lamont Geological Survey by Ewing and Donn and obtained a grant from

Blough's steel company for their research.

But he never forgot those early days. So here is the story Gramps wrote on hog butchering:

*************

Getting Early Start

Before dawn cracked or even came close to cracking, all hands were on deck. Regular chores were down in double time—milking, feeding, watering, separating.

Breakfast was bolted down in a whistle. Pig sty was given last cleaning out and washing, while the roused porkers eyed the activity with deep resentment and suspicion. “What! No feed today!”

Then the farm boy started pumping water, carried it in pails, filled three, four copper and or cast iron kettles and filled dozens of milk cans besides.

Kindling was doused with kerosene and fires were lighted and soon crackling and burning. Showers of sparks ascended in the dark or maybe as rosy-tinted dawn spread her first fingers—and the frosty air was set in circulation by the sudden invasion of thermal currents.

Wind barriers were readjusted to give maximum vertical output. Soon the water began to simmer and it was a full time job keeping the fires roaring. The stored woodpiles began to diminish in height and more was scoutched [sic] up, just to play safe.

From many directions the butchering helpers began to arrive, in buggies and in spring wagons. Neighbors and relatives, some from the cities. Merry greetings were passed. Then the forces moved on to their places of occupation: Women folks to the kitchen and shanties to prepare foods for the dinner, and the pots, pans and crocks for the puddin’ meat and the ponhos, while the men took their assignments from Uncle Ed, the boss butcher.

Shootin’ and Sitckin’

The men descended on the pigsty, armed with rifle and deer knife for sticking, while the young ones were told to stay back and keep the fires going. “You’re too little to watch shootin’ and stickin’.”

Soon you’d hear the crack of a rifle and maybe dead silence, but more likely an unearthly squealing. Perhaps the sty door would be opened and the dead pig dragged out. or maybe he’d come out “standing,” gushing blood from the severed jugular.

Maybe he’d drop dead all of a sudden, but like as not he’d take off up through the apple orchard with two, three hands in a merry chase. No one liked that, for it may mean a hundred yards dragging the carcass to the scalding barrel. Unusual work was undesired—usual work was sufficient.

“Get the water in the barrel!” All hands rushed to do so. It had to be real scalding hot to make bristle removal easy, yet not too scalding as to start the porker to cookin’.

“Refill the kettles!” And you’d do so, from the reserved milk cans. Or, run like blazes to the pump to get more in a hurry.

“More wood on the fire!” And hands and feet were really flying!

Into the barrel they shoved the head end of the now extinct porker, and sloshed him around. Water slopping on the ground melted the frost.

Testing the Bristles

“Pull him out, boys, and upend him!” Then they dipped the tail end. It was time for Uncle Ed to test the bristles. If they came out easily the “dip” was successful. If not, more scalding water was added until the bristles did come off just right.

“Up and over!” And so Pig No. 1 was ready for scrapping. Meanwhile the killers and stickers had another pig en route to the scalder—never a dull moment. Snout hooks and tendon hooks were used to handle the slippery porker, from scalder to scrapping table.

Then in a few moments scrapping knives began to clean off the bristles until the pig’s carcass was white and pink and gleaming, that is, from the ears backward.

“Okay, boys, on the head and at the feet.” These were choice areas reserved for the younger boys and grandfathers.

It was really an art to scrape the stiff, shorter bristles from the wrinkles around the pig’s snout and beady eyes, and from the deep wrinkles of his fat jowls and under his chin. Also from the creases of his stubby feet.

And these just had to be clean, for from them came the ponhos ingredients and choice pickled tidbits and for the souse. (Barbers could do better with Uncle Ed’s stubble, since his pink cheeks were at least a bit flexible.)

Heave Ho! Up You Go!

Within a few minutes all carcasses were promptly stretched out, inverted, on the ground, and leg tendons were freed for insertion of the tree hooks. With these inserted securely, there came the order, “Heave ho! And up you go!”

In a trice the pigs were swinging, pendulum-like, from the tripods. A deft slash of the knife in the belly area and the large intestines were removed and carted away in the wheelbarrow to the barnyard.

Soon every fowl and every bird, pigeon, swallow and sparrow on the farm was picking away at the odorous mess, as you hastened back for the next load.

Then the carcasses were washed thoroughly with pails of lukewarm water. Viscera and vital organs were deftly severed and removed, being placed in proper containers for further cleansing, trimming and cutting before cooking as ingredients for the choice dishes that grace the farm breakfast tables.

Specialists At Work

Then the head butcher, man of steady hand and keen eyes and of long experience, takes a double-bitted axe, previously sharpened by the farm boy, and deftly splits the disemboweled carcasses down both sides of the pig’s backbone.

Like all Gaul, the pig swings into three parts, whence now the sub-butchers each takes his parts to the trimming tables and proceeds to exercise his private specialty. One, the ham trimmer; one the flitch trimmer and rib-stripper; and one the shoulder man.

Each of the sides quickly becomes three parts, and each of these parts begins to assume familiar shapes and contours. Off come the feet, out come the ribs. The flitch, ham and shoulder get their artistic shapes under the practiced hands of masters, as each steps back to view the details of chiseling, shipping and trimming.

“More wood on the fires! More water in the kettles! Get out the lard cans and trimming cans from the stockpile. Come on there, boy, get moving!” Never a dull moment.

The division of labor now assumes new proportions. There are soft under-belly slabs of leaf lard—slippery as an eel and just as hard to hold and chop into squares. Stingy membranes to remove and cut through—of course that’s the boy’s job.

Then the nice firm fatty places must also be chipped. And the vital organs trimmed and cleansed. The meat scraps and firm suet-like pieces are sorted out for the sausage meat. Small intestines are drained and washed and taken into the shanty for “Nammie” to scrape, turn, scrape again and turn, wash scrape again—until every loose membrane is removed. Then these casings for the sausage are ready for the stuffing.

No barber with straight razor could ever approach the skill of the “Nammies” in intestine-scraping. They come out clean and clear as finest plastic, with nary a cut or even a pinhole, in yards of yards of the product.

Merrily the work went on. The play and the exchange of jokes saved for the occasion flew fast. Plans for the winter’s programs (even church suppers) all went hand-in-hand with the trimming and chipping and cutting.

“Nammie’s” Pigtails

Pig tails were traded from kinder to gown-up, but inevitably one or more found its way to “Nammie’s” skirt, as if she didn’t know it was affixed there while she wagged and wiggled for purposeful entertainment!

Meanwhile in the kitchen the air was blue and white with gossip and filled with savory odors of roasting stuffed chickens, beans and beets and cabbages and carrots and potatoes boiled. All simmered tantalizingly on every lid of the cast iron cooking ranges—one in the kitchen, another in the shanty.

Hands and tongues flew with abandon and soon the table was bent and buckled from the mounds of mashed spuds, bowls of giblet gravy and vegetable dishes, as well as celery and cabbage salad and cole slaw and pickles and eggs devilled in red beet juice and piccadilli and stuffed pickled peppers and spiced crabapples.

“Dinner is ready!” In flock the “hands” to the pump and basin—of nice cold water. Hands and faces find dry spots and places on the harsh linen roller towels. Out of the ovens come the roast chickens, the escalloped oysters, the baked squash and divers other items.

Grace is said and from there on you can use your imagination, since this is a butcherin’ dinner. Peach, pear, plum, cherry and apple pies with a variety of cakes are all standing by on every available shelf and table.

The little farm girls wait hand and foot on the men at the tables, sometimes giving some peculiar and special attention to certain farm boys of their choosing.

Meanwhile the cooks sit in the rockers and exchange quips and stories with the men and with one another. After the men are gone back to the butcherin’, they and the girls will eat at the second table.

Yards of Sausage

“Okay men, let’s go!” And out they troop, to wind up the work. “Fresh wood on the fires. Say, tame down those lard-kettle fires or you’ll burn the lard.” The lard stirrers begin to supervise the stirring and the fire-stoking so as to maintain just the correct heat for the simmering and rendering.

The puddin’ meat and ponhos cookers test the degree of doneness of the livers, hearts, tongues, kidneys, meat strips and head meat and the pig’s feet. “Boy! Taste that liver! Is it done enough to suit you?” And it usually is, but seems to require a good-sized chunk just to make sure.

Meanwhile as the chunk of liver cools, you are busy grinding the sausage meat, while “Pappy” salts and flavors and samples. Then he takes a tubful and starts the stuffing, stripping yards on the spot, yards and yards of smaller intestines. The press is turned and out flows the sausage.

“Nammie stands by and as the sausage emerges she kneads and squeezes and coils the product into another waiting tub. “Watch where you’re spitting tobacco juice, you old buzzard! We don’t want none in our stuffed sausage!”

Ponhos and Lard

Then the pig’s feet are extracted from the ponhos kettle and the chunks of vital organs are ground in the sausage grinder. The mess is stirred back into another waiting kettle. “Nammie” adds the spices and corn meal in just the right proportions—“a little of this and a little of that.” She keeps sampling the ponhos with over-sized wooden spoons just to be sure.

“Sausage stuffing all finished! Bring on the lard! Careful now! Don’t get scalded.” And the dippers and pails full of nicely toasted and rendered lard chunks go splashing into the sausage grinder, which this time has a large-holed inner liner to capture the lard chunks.

Press and squeeze till every bit of precious amber-fluid is out of the crispy brown pieces and gathered into the waiting lard cans. Then the pressed cakes are removed and stacked for the chickens to feed on this winter. (But are sampled quite extensively when cool enough!)

The brimful lard cans are allowed to cool a bit, then lids are placed on firmly. Then the ponhos, thoroughly cooked and just the right color, is poured into crocks and pans and a small quantity of lard poured on to seal the batch from the air. Each helper and neighbor, as well as city visitor, had bought his own pan for a helpin’.

Come Again Next Year

The chilled hams, shoulders, backbone chunks, flitches, et alia, are carried into the proper storage facility where further treatment such as pickling, smoking and preserving will occupy odd moments for following days and hours.

Clean up, wash up pails and pans and knives. Wipe up and scrape the tables and the cutting boards. Sweep up the bristles to dry and later be burned far away from dainty noses.

Douse the fires, clean the kettles. Store the hooks and the hangers and empty and wash out the scalding troughs and barrels.

“Okay now, boys! Let’s have a snifter of dandelion wine! And thanks a million. Be sure to stay for supper and also come again next year!” The helpers and neighbors thin out, to go home and do their own regular chores: feeding, watering, milking, separating.

The embers die down. The woodpile had disappeared. All is quiet. The butcherin’ has ended.

Lynne

*****

The articles appeared in Ben Meyer's column "We Notice That". Ben responded in the paper with this follow-up:

Dear Lynne:

Congratulations! That was a bang-up job of remembering the many varied details of a family butcherin’ such as was so common place hereabouts a generation or so back.

Our old-time readers, and doubtless many of the younger fry, will take keen delight in reading and re-reading your story of Uncle Ed and Aunt Carrie’s farm in Armagh Township.

Some of the old guard family butchers still do business at the old stand. But their number dwindles as time goes on. You may be sure their products are in great demand. People’s mouths drool just at the very thought of being presented with a mixture consisting of a ring of sausage in skins, a pan of ponhos (the main ingredients) and some side dishes like a generous slab of puddin’ meat, souse, et cetera.

Back in the old days we used to call such a present a “metzelsoup” down in Dauphin County where we came from. All the hands that so willingly pitched in and worked so hard found that such a hand-put as they departed for their homes that evening well repaid them for all the time and labor expended. Fortunate indeed were outsiders, such as neighbors who hadn’t participated, if they were remembered when one of the farm boys brought a metzelsoup to the door and said, “Here’s a present form pop ‘n mom!”

Certain of the old line butchers have parleyed the family butcherin’ into Big Business. They are the ones who supply home-made pork products in quantity, at wholesale rates to the local markets, including and especially the super-markets.

The Modern Version

Maybe some day while helping yourself at the magnificent display of packaged meats in the counter at the super-duper, you’ll see employees walking past with huge quantities of ponhos, sausage, puddin’ meat. They are being unloaded from a farm truck that’s backed up to the delivery door outside.

People around here still keenly relish the old-time flavor of home-made butchered goods so they demand it rather than to have the stuff shipped in from some packing house where they wouldn’t have the knack of making the stuff right anyhow.

Seems there’s one item in particular you can’t buy in most local retail stores and that is home-made souse. Only souse obtainable is some coarse, tough kind, very much commercialized and nothing like the real thing. Doesn’t taste any more like the real thing than shoe leather compared with a gold brown buckwheat cake!

Correction: Certain neighborhood stores still carry the home-made kind. Some of the local butchers operate little factories in their back yards. They can supply you with the real wiggly jiggly souse including plenty of pork and not bits of rind and bone and pig skin.

Yes, all of the things you mention are to be obtained too at Farmer’s Market where the vendors still include a small handful of Amish farmers. Thanks again, Lynne, for your masterpiece! Oh, yes you employed all the technical terminology of an old-time butchering, or almost all, but one work was missing—“cracklin’s!”

**************

Lynne Oliver Ramer's retirement announcement was not the end of his work life, as he continued teaching at LIT.

Chevrolet Engineering Retirement Announcement, July 23, 1965

This is to announce the forthcoming retirement of Lynne O. Ramer in the Design Analysis activity [electronics computers], which becomes effective September 1, 1965, ending an association of more than thirteen years of service with the Chevrolet Engineering organization.

Following his graduation from high school at Milroy, PA, Lynne attended Susquehanna University where he received a degree in Liberal Arts. Lynne later received a Masters degree in Math from the University of Buffalo. He also received a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Susquehanna University Theological Seminary and began teaching at Hartwick Academy. He was ordained a Lutheran minister in 1926.

Lynne started in the public school teaching profession as a teacher of history and math at Kane High School in Kane, PA 1920-30. From June 1942 to January 1946 Lynne was employed at the Chevrolet Aviation Engine Plant in Tonawanda, NY as an Engine Test Operator. He then returned to school teaching at the University of Buffalo and West Seneca High School. In January 1952, Lynne transferred to the Chevrolet Aviation Engine Plant as an Experimental Engineer. He was transferred to the Holbrook Test Laboratory in November 1953. In March 1955, Lynne was promoted to Senior Project Engineer. in January 1961, he became a Senior mathematician programmer, and in October 1962 was reassigned as a Senior Analyst, the position from which he will be retiring.

Lynne has also been a part time teacher since 1942. He has taught various night school, including University of Buffalo, Wayne State, and Lawrence Tech. He has also been very active in the church since June 1950 when he was ordained a perpetual deacon.

His future plans include teaching at Lawrence Tech and continuation as a Deacon in the church.