We Notice That

by Ben Meyers

The Heights Phone 8-8430

Dinkey Pix

Dear Ben: Here’s a letter from

Lynne Ramer that’s chockfull of interesting memories which many WNT

readers will enjoy. Got it after he read my letter in your column.

He requested use of a couple old-time pictures such as the dinkeys

and logging scenes in Seven Mountains. Intends to use them to

illustrate a story he wrote for Steel Facts magazine. Seems we

formed a friendship through the We Notice That column, for which I

must say “Thanks!” With best wishes, sincerely,

Reed W. Fultz

Mifflintown R. D. 1

[Editor’s

note: handwritten by LOR: “Died 1962”]

Gabfest by Mail

Dear Reed:

As chances of getting together for a personal gabfest are remote,

how about doing it by mail? So you’re one of the Fultz family?

Yeah, boy!—there’s a family name deeply seated in memory.

Fred

Fultz was my S[unday] S[school] teacher and our Sunday School superintendent for years at St.

Paul’s Lutheran. His brother Rob (Baker) Fultz sneaked me many a

baker’s dozen of cinnamon rolls, so I could eat the 13th

without Nammie Ramer or Aunt Annie Smithers catching on.

I can

recall when Fred ran a grocery store in the old Campbell Funeral

Parlors building. And how Uncle Charles Smithers used to tell me how

he and Andy McClintic* put a wooden casket together in short order.

I

remember innumerable visits to the old plaster house next to the Methodist Episcopal Church where my cousin Stella Diemer [Deamer]* lived. In the doctor’s

office [that is] still there now, a doctor saved one of our twin sons, Donald, at

the age of 10, from dying of jaundice. Donald and his twin David are

now 24. David’s been serving aboard a U. S. sub at Halifax, Nova

Scotia.

Down your

way, Reed, I have got a college classmate, Alice M. Rearick*, who teaches

either in Mifflin or Mifflintown schools. Please do me a big favor.

Steel Facts that goes out to 175,000 readers will publish my article

on “Iron Rails and Dinkeys on Appalachian Summits.” Won’t you

let me borrow your photos with the dinkey and the Milroy loggers to

illustrate it? Gilbert Shirk*, McVeytown R. D. 2, supplied me with

many facts for the write-up.

As for

Buzzie Peters, I knew him well. Also James (Fatty) Crissman* and the

stagecoach. I set the coach on fire one day while smoking dried

leaves and corn silk at the age of 8. He kicked my posterior and

Nammie [Grandmother Rachel Reed Ramer] strapped the same place. We used to pasture our cow in

Jimmy’s meadow.

I

remember C. W. Peters and Sons laid almost every concrete sidewalk in

Milroy, Reedsville, and elsewhere in the valley. You can still walk

all over the Peters name!

Up on the

flats in the a. m., picking huckleberries and picnic, then down on the

logs, with dinkey whistle screaming across the Hartman Bottom, “Get

supper ready--will be home soon!”

The old

acetylene headlamps *like a ghost in the dark! “Them days is gone

forever,” but not from memory. I just “loved” your letter in

the WNT column. Do write some more.

Along

with John Benjamin Boyer* of Milroy High I can never forget Miss Mary

Barefoot*, who gave me the classics in Latin and English. She was

just out of this world, and not easily forgotten.

Also the Rev. Martin Fansold, principal during World War I. He sent me off to Susquehanna University and the ministry, else I might never have gotten away from K. V. [Kishacoquillas Valley]. Probably would be working at SSW [Standard Steel Works] yet, as do Boozer Bobb [Gramp's cousin Lee Sidney Bobb], George and Walter Smithers [Gramp's cousins], etc. alia. Not a bad life either.

Also the Rev. Martin Fansold, principal during World War I. He sent me off to Susquehanna University and the ministry, else I might never have gotten away from K. V. [Kishacoquillas Valley]. Probably would be working at SSW [Standard Steel Works] yet, as do Boozer Bobb [Gramp's cousin Lee Sidney Bobb], George and Walter Smithers [Gramp's cousins], etc. alia. Not a bad life either.

I can

still recall Reikley Bros. Sawmill, the dam, the log chutes and the

whirling saws. Also uncle Charles Smither’s planing mill and cider

press.

wnt

Underground

Honeycomb

Laurel

Run sinks into the hill just below where Uncle Charles’s plum

orchard reached. And again down behind the Winegardner farm above

Naginey. There it plumb disappears. And a third place is the Big

Sink just below the bridge in Milroy, opposite the old gristmill and

below Rudy’s blacksmith shop.

There it

sings in the summer. At Winegartner’s it sinks in the spring when

waters are high. At the spot below the old plum orchard, the hole is

almost plugged up. The water goes in with a sucking noise.

Up the

valley, innumerable streams disappear. All come out at Honey Creek.

That means Big Valley is a veritable honeycomb. That’s why the

early settlers called it Honey Creek, i.e., honey out of the

honeycomb!

Uncle

Clyde Ramer and I used to sit and freeze all day Saturdays just to

catch a few mullet out of Honey Creek above Reedsville. I can

remember two old cable suspension bridges between Reedsville and

Honey Creek, which we used to ride on as kids.

We also

fished in Tea Creek above the mill which I hear just recently was

burned. I remember the old tollgate at a point near the mill. And

when cars couldn’t get around that corner to go towards Belleville.

Just to

see what kids miss today: Towpaths, log chutes, sinks,

huckleberry-picking, wild turkeys, “kettles” and “kitchens”

in the mountains, dinkeys, jackasses, whirling saws, literary

societies, cakewalks, Fourth of July and Decoration Day parades,

Barnum & Bailey’s circus parades, trolleys, Bird Rock. Now all

they have is TV!

Orris

Pecht*, the school teacher, farmer Charles McLelland*, and I used to

pitch hay together on Charlie’s farm on the Back Mountain road

beyond the Klinger farm. Charlie used to say, “The farmer, the

school teacher, and the preacher—three in one!” I saw Charles

just a few days before he died. Orris, as far as I know, is still

around. Anne Burkins, Charlie’s daughter, was my High School flame. (One

of them!) Best regards to all the Fultz clan.

*****

NOTES:

NOTES:

*The Fultz family records show that my grandfather's pen pal, Reed William Fultz was born in February 1904 and died March 1962 in Mifflintown, Juanita, Pennsylvania. At the time of his death, he worked for the American Viscose Corporation. Reed married Jessie Shotzberger.

The 1910 Census shows Reed living with his family: Harry R, age 25, a lumberman; Bessie J, age 24; Reed W. age 6; Arthur A. age 4; Charles age 3. Son Miles Forrest was born in Milroy, PA in 1909.

In 1919 Bessie died and the 1920 Census shows the children living with their maternal Ramsey grandparents on Treaster Valley Rd. in Milroy, PA. James R. Ramsey was a farmer married to Nancy M. Nellie, age one, and grandchildren Charles, Miles, and William lived with them.

The 1920 Census shows Reed living with wife Bessie M., age 25, and their daughter Olive M., age one and a half. Their home was valued at $1,800.

*Fred Cleveland Fulz (7/1888-10/1976) appears on the 1930 Armagh Census as a grocer, married to Blanche M. and father to children Geraldine P, age 17, and Elizabeth M, age 10. On the 1910 Census he appears working as a store clerk and living with his parents David Fultz, 48, and mother Catherine 48, and siblings Milton, 28, a baker, sister Ruth, and Bertha, a grandchild to David and Catherine.

*Stella Deamer (born July 31, 1883) was the daughter of Charles Ramsey and Emma Reed (1851-1909) who was his grandmother's ('Nammie' Rachel Reed Ramer) sister.

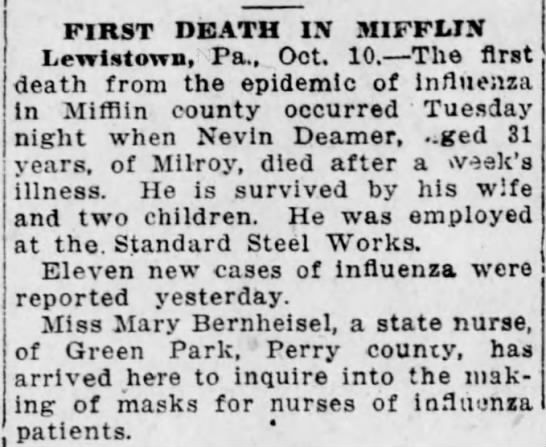

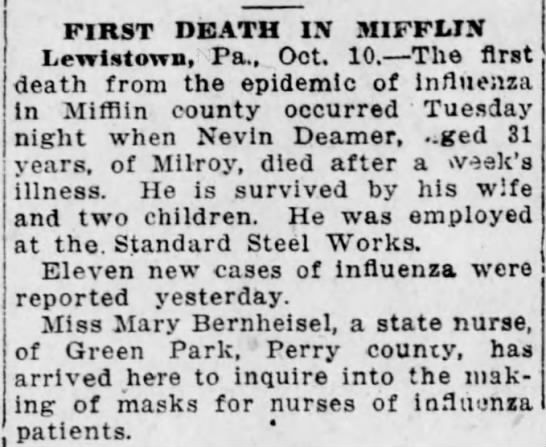

Stella married Nevin Ellsworth Deamer. His WWI Draft Card showed he worked for Standard Steel. They had two children, Perry and Francis. Nevin died on October 8, 1919, the first Mifflin County victim of the Influenza Epidemic.

The 1920 census shows Stella was a dressmaker.

Stella later married Thomas Peter Fultz who died in 1948. Stella died July 25, 1945, in Burnham, Mifflin County, PA.

The Methodist Episcopal Church (now United Methodist) is located at 91 S. Main St, Milroy PA.

*Andrew 'Andy' Felix McClintock (b. 10/9/1948, d.9/26/1915) appears on the 1910 Armagh, Milroy Census with his wife Ada Jane Crissman (1861-1921). Find A Grave had the entire family including Andy's parents Rosanna (1811-1890) and father Felix (1802-1883) and his siblings. Andy's grandfather James (1782-1834) served in the American Revolution.

*Alice M. Rearick was Gramp's Susquehanna University classmate in the class of 1924.

She appears in the 1922 Lanthorn as Omega Delta Sigman member.

Alice was on the Lanthorn Staff when Gramps was editor-in-chief.

*Mary Margaret Barefoot, my grandfather's teacher, was born April 12, 1890, to William and Mary Sterrett Barefoot. On October 11, 2910, the forty-year-old Mary married Albert Vincent Landgren, an electrical engineer. She died on July 16, 1981 in Canton, OH.

*Orris Wilmot Pecht (1873-1964) was a farmer on 1910 census and a schoolteacher on his WWI Draft Card and the 1920 census.

*There is a Charles Edward McLelland (1875-1941) whose death certificate shows he was a retired farmer and married Hannah Pecht.

But I can't find a daughter Anne in the records.

*Anna M. Burkins (1900-1993) appears in the records as a schoolteacher. On Find A Grave, her parents appear as David Riley Burkins and Mary McLenahen.

Anna taught history in Lewistown High School.

I find a *Charles McClenahen (1807-1849) who married Agnes Wingate who had son John Ambrose McClenahen (1846-1901) who married Anna Bertha Geer and they had daughter Anna Mae. Either Gramps was misremembering names or his handwriting was misunderstood when the newspaper printed his letter.

*Fred Cleveland Fulz (7/1888-10/1976) appears on the 1930 Armagh Census as a grocer, married to Blanche M. and father to children Geraldine P, age 17, and Elizabeth M, age 10. On the 1910 Census he appears working as a store clerk and living with his parents David Fultz, 48, and mother Catherine 48, and siblings Milton, 28, a baker, sister Ruth, and Bertha, a grandchild to David and Catherine.

*Stella Deamer (born July 31, 1883) was the daughter of Charles Ramsey and Emma Reed (1851-1909) who was his grandmother's ('Nammie' Rachel Reed Ramer) sister.

Stella married Nevin Ellsworth Deamer. His WWI Draft Card showed he worked for Standard Steel. They had two children, Perry and Francis. Nevin died on October 8, 1919, the first Mifflin County victim of the Influenza Epidemic.

The 1920 census shows Stella was a dressmaker.

Stella later married Thomas Peter Fultz who died in 1948. Stella died July 25, 1945, in Burnham, Mifflin County, PA.

The Methodist Episcopal Church (now United Methodist) is located at 91 S. Main St, Milroy PA.

*Andrew 'Andy' Felix McClintock (b. 10/9/1948, d.9/26/1915) appears on the 1910 Armagh, Milroy Census with his wife Ada Jane Crissman (1861-1921). Find A Grave had the entire family including Andy's parents Rosanna (1811-1890) and father Felix (1802-1883) and his siblings. Andy's grandfather James (1782-1834) served in the American Revolution.

*Alice M. Rearick was Gramp's Susquehanna University classmate in the class of 1924.

Alice was in the Y.W.C.A. in 1923.

She appears in the 1922 Lanthorn as Omega Delta Sigman member.

Alice was on the Lanthorn Staff when Gramps was editor-in-chief.

*Gilbert M. Shirk began writing to my grandfather after reading his articles in the Lewiston Sentinel. He was a 'relation' through Gramp's natural father. Gil and Gramps met once when they were children.

* James Meade Crissman (1863-1923), son of John McDowell Crissman and Mary Jane Aikens, owned a stable in Milroy and the 1920 census shows he was a "drayman" and mail carrier. James married Mary Sterrett in 1895.

*Acetylene gas headlamps on trains and automobiles were used beginning around 1901. Learn more here.

*John Benjamin Boyer (1883-) was a 1908 graduate of Bucknell University.

I found his WWI registration card.

*Mary Margaret Barefoot, my grandfather's teacher, was born April 12, 1890, to William and Mary Sterrett Barefoot. On October 11, 2910, the forty-year-old Mary married Albert Vincent Landgren, an electrical engineer. She died on July 16, 1981 in Canton, OH.

*Orris Wilmot Pecht (1873-1964) was a farmer on 1910 census and a schoolteacher on his WWI Draft Card and the 1920 census.

*There is a Charles Edward McLelland (1875-1941) whose death certificate shows he was a retired farmer and married Hannah Pecht.

But I can't find a daughter Anne in the records.

*Anna M. Burkins (1900-1993) appears in the records as a schoolteacher. On Find A Grave, her parents appear as David Riley Burkins and Mary McLenahen.

Anna taught history in Lewistown High School.

I find a *Charles McClenahen (1807-1849) who married Agnes Wingate who had son John Ambrose McClenahen (1846-1901) who married Anna Bertha Geer and they had daughter Anna Mae. Either Gramps was misremembering names or his handwriting was misunderstood when the newspaper printed his letter.