As the Detroit Symphony Orchestra concert was airing on Livestream I opened my ebook and began to read. I was soon laughing out loud. A few paragraphs later I laughed even longer and harder. I had to read out loud to my hubby. And then I knew. I could not read Calypso by David Sedaris while listening to the symphony.

I could not read it in bed. I would laugh my husband awake. When could I read it? During the day, with the windows open to let in the fresh spring air, so inviting after a very, very, long winter? What would the neighbors think?

Sedaris, Sedaris. You are such a problem, I thought.

Then I felt like I was on a roller coaster ride because the next story was about David's youngest sister's suicide. All of the siblings had pulled away from the family to "forge our own identities," he explained; except Tiffany stayed away. And later in the book, he remembers his mother's alcoholism and her early death, his father's eccentricities, living with a defunct stove so his kids could inherit more money.

You laugh, you shudder, you feel slightly ill, and you feel sad. Because Sedaris is ruthless enough to write about life, real life, his life in particular, and we all see our own families and own lives in his stories.

I loved Sedaris's chapter on the terrible tyranny of his Fitbit, and how he was adamant that he got to keep his fatty tumor to feed to a turtle. That crazy moment with his dad drove past a man exposing himself and then u-turned to take another look, his young daughter in the car.

Looking at family photos, Sedaris recalled "that moment in a family's life when everything is golden" and the future held promise. In middle age, looking forward ten years "you're more likely to see a bedpan than a Tony Award."

Ouch. Too close to home, David.

I received a free ebook from the publisher through NetGalley in exchange for a fair and unbiased review.

Calypso

by David Sedaris

Little, Brown and Company

Pub Date 29 May 2018

ISBN 9780316392389

PRICE $28.00 (USD)

Saturday, May 12, 2018

Friday, May 11, 2018

Lighting the Fires of Freedom: African American Women in the Civil Rights Movement

Fifty years ago the Civil Rights Act of 1968 was signed into law.

Most know the name, legacy, and speeches of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King.

And most have heard of his wife Coretta Scott King and activist Rosa Parks. But what about the countless other women involved with the Civil Rights Movement? Those who did the grunt work, who put their lives on the line, who strove to achieve what the culture said they could not do?

Getting Personal

When I made my quilt I Will Lift My Voice Like a Trumpet I was inspired by the Abolitionists and Civil Rights who I encountered in reading Freedom's Daughters by Lynne Olson. My embroidered quilt includes an image and quote from women who made a difference but are not well known. The quilt appeared in several American Quilt Society juried shows.

When I saw Lighting the Fires of Freedom: African American Women and the Civil Rights Movement by Janet Dewart Bell on NetGalley I quickly requested it. I was interested in meeting more of these courageous, but lesser-known women.

Going Deeper

The author interviewed and collected oral histories of nine women for this book:

I was familiar with Diane Nash, who appears on my quilt. I only knew Myrlie Evers-Williams by association to her martyred husband Medgar.

For me, Evers' statement was most moving, revealing more about her emotional life and feelings. Her husband Medgar, a war veteran, was the first African American to apply to Ole Miss when he was recruited to work for the NAACP.

Myrlie organized events, researched for speeches, and even wrote some speeches while raising their family and welcoming visitors such as Thurgood Marshall to her home for dinner. It was a lot for a young woman. She is quoted as saying,

"It was an exciting but frightening time, because you stared at death every day...But there was always hope, and there were always people who surrounded you to give you a sense of purpose."

Medgar knew he was a target and encouraged her to believe in her strength.

After her husband was murdered in front of their own home, the NAACP would call on her to rally support and raise money, with no compensation. Meanwhile, she felt anger and outrage at what had happened. Medgar had dreamt about relocating to California some day, so Myrlie and her children moved.

Thinking back on the movement, Myrlie recognizes the struggle women had to be recognized for their work. And she bristles at being pigeonholed as Medgar's widow instead of being recognized for her accomplishments. It is wonderful that Myrlie was asked to deliver the prayer before President Obama's inaugural address.

Faith and trust and believe she ends, possibilities await. Be open. Be adventurous. Have a little fun.

That is good advice to us all. But coming from a woman whose husband made the ultimate sacrifice, it is an affirmation of great importance.

I received a free ebook from the publisher through NetGalley in exchange for a fair and unbiased review.

Lighting the Fires of Freedom: African American Women in the Civil Rights Movement

by Janet Dewart Bell

The New Press

Pub Date 08 May 2018

ISBN 9781620973356

PRICE $33.99 (CAD)

Most know the name, legacy, and speeches of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King.

And most have heard of his wife Coretta Scott King and activist Rosa Parks. But what about the countless other women involved with the Civil Rights Movement? Those who did the grunt work, who put their lives on the line, who strove to achieve what the culture said they could not do?

Getting Personal

When I made my quilt I Will Lift My Voice Like a Trumpet I was inspired by the Abolitionists and Civil Rights who I encountered in reading Freedom's Daughters by Lynne Olson. My embroidered quilt includes an image and quote from women who made a difference but are not well known. The quilt appeared in several American Quilt Society juried shows.

|

| I Will Lift My Voice Like a Trumpet at the Grand Rapids AQS show |

Going Deeper

The author interviewed and collected oral histories of nine women for this book:

- Leah Chase, whose restaurant was a meeting place for organizers, was a collector of African American art and was commemorated by Pope Benedict XVI for her service.

- Dr. June Jackson Christmas broke race barriers to gain admittance to Vassar, spoke out against the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII, was the only black female student in her medical school class, and fought housing discrimination to change New York City Law.

- Aileen Hernandez became an activist at Howard University in the 1940s, was the first female and black to serve on the EEOC in 1964, and was the first African American president of NOW.

- Diane Nash chaired the Nashville Sit-In Movement and coordinated important Freedom Rides.

- Judy Richardson joined the Students for a Democratic Society at Swarthmore College before leaving to join SNCC. She founded a bookstore and press for publishing and promoting black literature and was an associate producer for the acclaimed PBS series Eyes on the Prize.

- Kathleen Cleaver was active in SNCC, the Black Power Movement, the Black Panthers, and the Revolutionary People's Communication Network.

- Gay McDougall was the first to integrate Agnes Scott College; she worked for international human rights and was recognized with a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship.

- Gloria Richardson was an older adult during the movement, with a militant edge; Ebony magazine called her the Lady General of Civil Rights.

- Myrlie Evers's husband Medgar was the first NAACP field secretary in Mississippi. She was officially a secretary, but she 'did everything' and later championed gender equality.

|

| Diane Nash. "Problems lie not as much in our action as in our inaction." |

For me, Evers' statement was most moving, revealing more about her emotional life and feelings. Her husband Medgar, a war veteran, was the first African American to apply to Ole Miss when he was recruited to work for the NAACP.

Myrlie organized events, researched for speeches, and even wrote some speeches while raising their family and welcoming visitors such as Thurgood Marshall to her home for dinner. It was a lot for a young woman. She is quoted as saying,

"It was an exciting but frightening time, because you stared at death every day...But there was always hope, and there were always people who surrounded you to give you a sense of purpose."

Medgar knew he was a target and encouraged her to believe in her strength.

After her husband was murdered in front of their own home, the NAACP would call on her to rally support and raise money, with no compensation. Meanwhile, she felt anger and outrage at what had happened. Medgar had dreamt about relocating to California some day, so Myrlie and her children moved.

Thinking back on the movement, Myrlie recognizes the struggle women had to be recognized for their work. And she bristles at being pigeonholed as Medgar's widow instead of being recognized for her accomplishments. It is wonderful that Myrlie was asked to deliver the prayer before President Obama's inaugural address.

Faith and trust and believe she ends, possibilities await. Be open. Be adventurous. Have a little fun.

That is good advice to us all. But coming from a woman whose husband made the ultimate sacrifice, it is an affirmation of great importance.

I received a free ebook from the publisher through NetGalley in exchange for a fair and unbiased review.

Lighting the Fires of Freedom: African American Women in the Civil Rights Movement

by Janet Dewart Bell

The New Press

Pub Date 08 May 2018

ISBN 9781620973356

PRICE $33.99 (CAD)

Thursday, May 10, 2018

Warlight by Michael Ondaatje

From the opening line, I fell into under the spell of Nathaniel's story about how he and his sister Rachel were abandoned at ages fourteen and sixteen to the care of relative strangers, their third-floor lodger, whom they called The Moth, and the Pimlico Dancer.

After their father departed, going to Asia for his work, never to be seen again, their mother stayed with them for two more weeks, sharing bits of her history, enough to lure them into understanding there was much more to her than they knew. Then suddenly she left them, too.

The Moth welcomes shady company into their home. The Darter brings a string of women, none of whom last long. The teens are left alone, sometimes for days.

Nathaniel discovers their mother's trunk is in the house. She had not left to join her husband. And The Moth wasn't talking. "He was brilliant," The Moth says of their father, "but he was not stable." Both parents are strangers to the teens.

Over the next years, Nathaniel lives in a complicated and uncertain world, accompanying The Darter on nighttime trips that are perhaps criminal activities, and working odd jobs during the day. He has a secret liaison with a girl in empty houses.

Years later, Nathaniel is approached to work in a government position that allows him access to files which he plumbs for information about his mother's war-related work. He visits people from his past. He pieces together who his mother truly was, the life she kept secret, the fear she lived with, and the lover who brought her into a world of danger.

Warlight is about a man's search for his mother, the story of the deeply etched marks left by a lost childhood, and an exploration of the stories we weave together just to survive.

I received a free ebook from First to Read.

Warlight

by Michael Ondaatje

Hardcover $26.95

Published by Knopf

May 08, 2018

ISBN 9780525521198

Tuesday, May 8, 2018

Winston Graham's Disturbing Suspense Novel Marnie

A few years ago we went to see Alfred Hitchcock's movie Marnie at the Redford Theater, a historic theater with an organ that shows classic movies. The theater is located in Detroit draws hundreds out for every show.

We went partly because Tippi Hedron was appearing in person, with talks before the movie and during intermission and autographing photos and posters. And we went because when I was ten years old I saw Marnie from the back seat of our family car at the local drive-in movie theater. I was supposed to be asleep. Just like when I was supposed to be asleep during The Birds and The Incredible Shrinking Man. Each movie left me with bad dreams, but it was Marnie that left me struggling to understand it.

So when at a local book sale I saw a battered paperback of Winston Graham's novel Marnie, released in conjunction with Hitchcock's movie, I spent my quarter and picked it up. Perhaps the book would help me to peg down the story.

Graham is best known for the Poldark series which inspired the Masterpiece Theater series of that name, which my husband has been reading. Marnie is set in England not long after WWII, and is told in the first person. We learn that Marnie grew up in a tough neighborhood with a dad lost in the war and a strict but distant mother. Marnie gets into fights and steals and lies. Her mother insists her daughter avoid men.

When Marnie buys a horse she must find a way to support him, and being a smart gal, she plans and executes a series of thefts, assuming false identities to obtain jobs where she can get her hands on money. She is twenty-three when she has finished another heist and her employer Mark Rutland tracks her down.

Mark has fallen in love with the beautiful Marnie. She warns him that she is a liar and thief, but Mark insists he can't control his heart. He offers her an ultimatum: he can turn her in and she will be imprisoned for her crimes, or she can marry him and he will cover for her.

Marnie can't stand to be close to anyone, is unable to love, and hates the thought of men and sex. Her horse is the only creature in the world she cares for. Forced to marry Mark, she won't submit to him as a wife should. Frustrated, he forces himself on her once, then they learn to live together in distant animosity and distrust.

Mark forces Marnie into counseling, but she is too clever for even the psychologist, continuing her habit of lies and false stories. Over time, men recognize Marnie from her past lives. And at the death of her mother, Marnie learns her mother's secret history and double life.

Different from Hitchcock's version, Graham's version of the mother's crisis is not of Marnie's doing. And Graham includes a co-worker of Mark's who tries to cozy up to Marnie, and ends up betraying her.

Marnie is one messed up girl, but Mark is perhaps even sicker. He marries Marnie for her physical beauty in spite of her inability to feel emotion that allows her to plot crimes without a sense of wrongdoing. He entraps Marnie and even rapes her when she is not complicit. He is willing to cover up her crimes and endeavors to even enlist the help of a retired judge to figure out how Marnie can avoid the consequences of her crimes.

Marnie returns to her mother's house to discover she has died. She finds a newspaper clipping telling that her mother had murdered her newborn baby, which had been kept from Marnie.

Graham offers a moment of hope for Marnie near the end of the book. At a fox hunt, she feels revulsion of the cruelty of those around her, questioning why their killing for pleasure was legal when her crimes would merit jail. She turns from the death scene of the fox, allowing her horse his head, Mark chasing after her. Unfamiliar with the landscape, her horse jumps over a hedge and onto a riverbank, suffering a fatal injury. Marnie also falls, and so does Mark, his face in the mud. Marnie leaves her suffering horse to save Mark, lifting him from the mud and wiping it from his nose. There is a glimmer of morality and compassion in her choice.

She later meets a bereft boy who has lost his mother and she holds him.

Just before the twisted ending, Marnie, feeling all 'emotional and female and hopeless,' wonders if she was in love with Mark.

Marnie is the story of trauma, mental illness, crime, deception, and a man's sick obsession with a woman.

It is little wonder that I have been disturbed by this story for about fifty years. And it is little wonder that the twisted Hitchcock wanted to film it. Poor Tippi-- Hitchcock derailed her career when she rebuffed his sexual advances. Her studio contract gave her no options, including legal ones.

Fifty years later, Tippi at age 87 cheered the actresses standing up against the abuse suffered under Harvey Weinstein, as seen in her Tweet of October 2017:

Now I am filled with compassion and respect for Tippi's standing up to power, speaking out her truth, and for introducing a film that was at once her triumph and secret tragedy.

We went partly because Tippi Hedron was appearing in person, with talks before the movie and during intermission and autographing photos and posters. And we went because when I was ten years old I saw Marnie from the back seat of our family car at the local drive-in movie theater. I was supposed to be asleep. Just like when I was supposed to be asleep during The Birds and The Incredible Shrinking Man. Each movie left me with bad dreams, but it was Marnie that left me struggling to understand it.

So when at a local book sale I saw a battered paperback of Winston Graham's novel Marnie, released in conjunction with Hitchcock's movie, I spent my quarter and picked it up. Perhaps the book would help me to peg down the story.

Graham is best known for the Poldark series which inspired the Masterpiece Theater series of that name, which my husband has been reading. Marnie is set in England not long after WWII, and is told in the first person. We learn that Marnie grew up in a tough neighborhood with a dad lost in the war and a strict but distant mother. Marnie gets into fights and steals and lies. Her mother insists her daughter avoid men.

When Marnie buys a horse she must find a way to support him, and being a smart gal, she plans and executes a series of thefts, assuming false identities to obtain jobs where she can get her hands on money. She is twenty-three when she has finished another heist and her employer Mark Rutland tracks her down.

Mark has fallen in love with the beautiful Marnie. She warns him that she is a liar and thief, but Mark insists he can't control his heart. He offers her an ultimatum: he can turn her in and she will be imprisoned for her crimes, or she can marry him and he will cover for her.

Marnie can't stand to be close to anyone, is unable to love, and hates the thought of men and sex. Her horse is the only creature in the world she cares for. Forced to marry Mark, she won't submit to him as a wife should. Frustrated, he forces himself on her once, then they learn to live together in distant animosity and distrust.

Mark forces Marnie into counseling, but she is too clever for even the psychologist, continuing her habit of lies and false stories. Over time, men recognize Marnie from her past lives. And at the death of her mother, Marnie learns her mother's secret history and double life.

Different from Hitchcock's version, Graham's version of the mother's crisis is not of Marnie's doing. And Graham includes a co-worker of Mark's who tries to cozy up to Marnie, and ends up betraying her.

Marnie is one messed up girl, but Mark is perhaps even sicker. He marries Marnie for her physical beauty in spite of her inability to feel emotion that allows her to plot crimes without a sense of wrongdoing. He entraps Marnie and even rapes her when she is not complicit. He is willing to cover up her crimes and endeavors to even enlist the help of a retired judge to figure out how Marnie can avoid the consequences of her crimes.

Marnie returns to her mother's house to discover she has died. She finds a newspaper clipping telling that her mother had murdered her newborn baby, which had been kept from Marnie.

Graham offers a moment of hope for Marnie near the end of the book. At a fox hunt, she feels revulsion of the cruelty of those around her, questioning why their killing for pleasure was legal when her crimes would merit jail. She turns from the death scene of the fox, allowing her horse his head, Mark chasing after her. Unfamiliar with the landscape, her horse jumps over a hedge and onto a riverbank, suffering a fatal injury. Marnie also falls, and so does Mark, his face in the mud. Marnie leaves her suffering horse to save Mark, lifting him from the mud and wiping it from his nose. There is a glimmer of morality and compassion in her choice.

She later meets a bereft boy who has lost his mother and she holds him.

"I thought, that's right, be a mother for a change. Bite on somebody else's grief instead of your own. Stop being to heartbroken for yourself and take a look round. Because maybe everybody's griefs arent'that much different after all. I thought, there's only one loneliness, and that's the loneliness of all the world."

Just before the twisted ending, Marnie, feeling all 'emotional and female and hopeless,' wonders if she was in love with Mark.

Marnie is the story of trauma, mental illness, crime, deception, and a man's sick obsession with a woman.

It is little wonder that I have been disturbed by this story for about fifty years. And it is little wonder that the twisted Hitchcock wanted to film it. Poor Tippi-- Hitchcock derailed her career when she rebuffed his sexual advances. Her studio contract gave her no options, including legal ones.

Fifty years later, Tippi at age 87 cheered the actresses standing up against the abuse suffered under Harvey Weinstein, as seen in her Tweet of October 2017:

Now I am filled with compassion and respect for Tippi's standing up to power, speaking out her truth, and for introducing a film that was at once her triumph and secret tragedy.

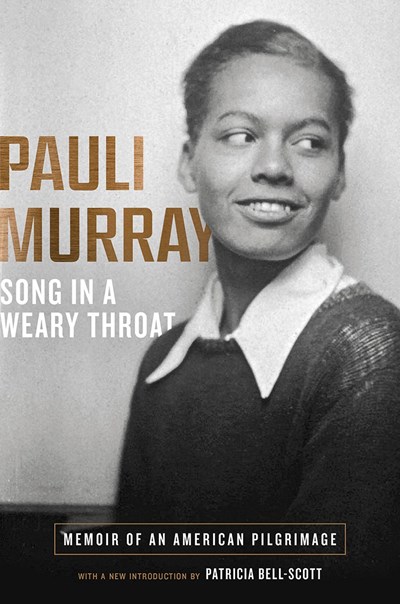

Pauli Murray: Poet, Protester, Priest

Pauli was born in 1910 and was raised by her school teacher aunt. Pauli was a gifted student who attended Hunter College in New York City. During the Depression, she found employment with the WPA as a teacher and began to publish her poetry and a novel. She found a mentor in Stephen Vincent Benet.

During the war years and early 1950s Pauli became involved with Civil Rights, challenging segregation, and formed a relationship with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1941 she began her law studies at Howard University and helped to form CORE and the development of passive resistance.

Harvard law school would not accept Pauli based on her sex. She attended the University of California Boalt School of Law. Her thesis was on equal opportunity in employment. With her color and sex against her, Pauli had trouble making a living practicing law.

In 1956 she published a book on her family history, Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family. She taught law in Ghana for several years. Back in the US she resumed work in Civil Rights and became active as a feminist and was an organizer for NOW.

In her later life, Pauli worked for equal opportunity for women as church leaders. She became the first African American woman ordained to the Episcopal priesthood.

Pauli saw huge changes in her lifetime. At her birth, she was labeled colored but chose to use the designation Negro. During the rise of black power movements, she resisted the term black, resenting its lowercase nomenclature. She was a pacifist and anti-segregationist who had trouble with the rise of Black Power movements and the younger generation's demands for separate campus organizations. Early she was attracted to Socialism and spent her last years as in the priesthood.

The memoir is filled with details about the work for Civil Rights prior to the more known stories of Rosa Park and Martin Luther King, Jr. There are vivid descriptions of traveling in the Jim Crow south, the closed doors to her race and her sex, the poverty she and her educated family endured.

Pauli's voice is direct and open. She admits to her ignorance and mistakes, her learning curves and limitations. Her accomplishments speak for her determination and courage.

It was wonderful to hear, in her own voice, Pauli's amazing life.

I received a free galley from the publisher through Edelweiss in exchange for a fair and unbiased review.

|

| Pauli Murray on my quilt I Will Lift My Voice Like a Trumpet |

|

| I Will Lift My Voice Like a Trumpet by Nancy A. Bekofske |

From the publisher:

Poet, memoirist, labor organizer, and Episcopal priest, Pauli Murray helped transform the law of the land. Arrested in 1940 for sitting in the whites-only section of a Virginia bus, Murray propelled that life-defining event into a Howard law degree and a fight against “Jane Crow” sexism. Her legal brilliance was pivotal to the overturning of Plessy v. Ferguson, the success of Brown v. Board of Education, and the Supreme Court’s recognition that the equal protection clause applies to women; it also connected her with such progressive leaders as Eleanor Roosevelt, Thurgood Marshall, Betty Friedan, and Ruth Bader Ginsberg. Now Murray is finally getting long-deserved recognition: the first African American woman to receive a doctorate of law at Yale, her name graces one of the university’s new colleges. Handsomely republished with a new introduction, Murray’s remarkable memoir takes its rightful place among the great civil rights autobiographies of the twentieth century.

Learn more about Murray at The Pauli Murray Project at the Duke Human Rights Center.

Song in a Weary Throat: Memoir of an American Pilgrimage

Pauli Murray, Patricia Bell-Scott (Introduction by)

Liveright/W. W. Norton

On Sale Date: May 8, 2018

ISBN: 9781631494581, 1631494589

Paperback $22.95

Monday, May 7, 2018

An Interview with Ellen Notbohm

I had the pleasure of talking to Ellen Notbohm about her first novel The River by Starlight, published by She Writes Press.

from the author's website:

She meets Adam who is drawn to her fiery strength and quick mind. They marry and settle down to farm, at first prospering but later hit by climate change. Mental health issues follow a series of losses, including miscarriages and the death of a child, resulting in Annie's institutionalization. Yet Annie rises again to cobble together a meaningful life.

The book is a wonderful read, with sympathetic, conflicted. characters, snappy dialogue, and a vivid Montana setting. Through Annie's life, the novel considers how women's health issues have been treated in a patriarchal society. (Read my full review here.)

Annie's love for Adam is represented by a marriage quilt she made for his eyes only. She creates an quilt that displays her independent mind and spirit. Because I am a quilter, I began by asking about the quilt.

Nancy:

The quilt Annie makes Adam is a symbol of their connection and shared life. Please talk about how the quilt came into the story.

Ellen:

This question goes right to the intersection between writing fiction and drawing from true story. You have lots of facts and lots of gaps. You have to listen for direction with your third ear, as I call it.

I don’t know how the quilt came into the story; it just did. Knowing so little about Annie when I decided to write her story, I read extensively about the places she lived and the times during which she lived in those places. Piecing that research together—like a quilt—with the insights and information I was gathering about her and Adam specifically, I began to construct their world.

The quilt grew out of that, and how it grew! It became a touchstone for so many things. A symbol of their intimacy, as Annie won’t let anyone other than Adam see the quilt. A stark representation of gender differences, as Annie and Adam view the quilt’s role in their lives differently, as it exerts a different kind of power over each of them. And ultimately, the quilt becomes a standard bearer for resilience and hope.

Annie’s quilt isn’t the only one in the book. We learn that as a young girl, Annie was dismayed by the traditional wedding quilt made for her sister by friends—the neutral colors and strict symmetry of the tree pattern defied what Annie already knew to be true of life’s uneven trajectory. Her own vibrant quilt would be her counterpoint to that.

Later in the book she encounters a very old quilt which also carries a message she needs to hear but almost misses. We also learn that she made her brother a quilt, “no-nonsense patchwork of duck cloth, corduroy, and denim” heavy enough to “keep her in her place” when she uses it.

Nancy:

There are detailed descriptions of the fabrics Annie chooses which are correct to their time, and not all novelists who include quilts in their stories are aware of fabric and quilt history. Is Annie's quilt based on any historic quilts you have seen? Did you research quilting in the early 1900s?

Ellen:

Yes. The fabrics and colors described are authentic to the day. The traditional patterns Annie rejected—Log Cabin, Bear Paw, Wedding Ring, Crazy Quilt—were also authentic to the period. Annie’s quilt, The River by Starlight, is free-form, which didn’t become popular until much later, perhaps the 1970s.

In fiction, the writer can explore beyond the confines of what is actual, to what is plausible. It felt plausible to me that Annie would have come up with her own design, depicting a moment that would define the rest of her life. In moving to Montana, she broke free of so many of the constrictive elements of her life up to that point, it made sense to me that the quilt she conceived for a wholly unexpected turn of events would be somewhat daring.

She also broke with tradition in buying all new fabric for her quilt. In her time and economic class, quilts were most often pieced from fabric scraps of previous projects—dresses, shirts, curtains, etc. In a passage that, alas, was lost to the editing process,

Annie makes a “decadent” decision:

I thoroughly enjoyed the book Border to Border: Historic Quilts and Quiltmakers of Montana by Annie Hanshew. It didn’t influence my writing about my Annie’s quilt, as I was already several years deep into the writing about it. But the cover of the book did inspire me to write a scene wherein, at the end of her life, Annie makes a quilt for her daughter as a wedding gift. That one too fell to the editor’s knife, alas. But it lives on in my heart, so who knows where it might show up?

Nancy:

I read that you are a genealogist and that the novel is based on a true story. I would love to know about the inspiration story and how you decided to write about it. Did the actual people 'come to life' in your mind's eye?

Ellen:

Genealogists are familiar with the “brick wall.” Every family has one—the person that no one will talk about. There’s usually an aura of disgrace or taboo hanging around that silence.

Annie was the person behind the brick wall in my family tree. I saw her as a woman and a mother and a person whose blood runs in the veins of my children, and I felt compelled to know her story. I had only one little crumb of information to go on, but I sent that crumb on countless goose chases until I finally broke through the brick wall.

The root of those generations of zipped lips—perinatal and postpartum mental illness in an age of extreme gender disparity and social stigma born of ignorance. It demanded that I tell Annie’s story. The actual people did come vividly to life, not so much in my mind’s eye as in my heart.

Nancy:

I also do genealogy and spent ten years researching a 1919 diary and have more pages of research than diary pages! I have wondered how to present the woman behind the diary. So I am interested in knowing more about your handling of the historical records that became your novel. How do you transform the “cold facts” found on a census or death certificate into a narrative or character?

Ellen:

The common thread in all historical records is that they were recorded by people, and in every era, people have been influenced in their thoughts and actions by the conditions of the moment and of the times in which they live.

The “cold facts” found on censuses or death certificate are frequently not as immutable as we may think—information is only as good as the person who gave it and the person who recorded it, and human fallibility is itself a cold fact. The person giving the information may not have the correct info, and the person recording it may be in a hurry, not feeling well, indifferent to accuracy, distracted by any the things that can distract us on the job.

In the case of older censuses, it wasn’t uncommon for family members or even neighbors to give information about individuals who weren’t at home when the census taker came around. That’s why you’ll find that census info on the same person over several decades of will show a variety of birthdates, birthplaces, spellings of names, immigration dates. Death certificates are also open to bias and error. The informant on a death certificate could be anyone from a close relative who either did or didn’t know the deceased well (children often didn’t know their parents’ origins), to a harried hospital or nursing home staffer who guessed at info or recorded hearsay. Records often contradict one another, so which one is the “cold fact”?

Historical documents are starting points, to which we must always search for context. It’s the context of the events of a life and how it shaped that person, not mere facts, that make a compelling story.

Of course, it’s nigh impossible to reconstruct the context of every event of an entire life. That’s where the author must decide where on the literary spectrum to take the story. I originally conceived Annie’s story as creative nonfiction. But the gaps and contradictions in the historical records shimmered with mirage-like questions of why? and how? Unexpectedly, fiction became the format through which I could best explore those questions and tell her tale.

Nancy:

Your previous books were nonfiction. The River by Starlight has beautiful writing and delves into intense emotions. What were the challenges and joys of working in fiction?

Ellen:

My nonfiction writing wasn’t without deep emotion and engaging writing, so it was a kind of training ground, especially my history articles for Ancestry magazine, many of which sprang from my research for The River by Starlight.

An editor once groused, “I hate the fact that you hook me all the damn time with your heart-wrenching stuff.” The challenge for me in writing fiction about real people was, am I portraying the message they would have wanted? How do I reconcile that, in the name of literary license, some collateral characters based only loosely on real people may be nothing like those real people, for better or worse?

The joy came from venturing to places previously unimagined, whether in my six research trips across Montana, North Dakota and Alberta, or in the vivid places I went in flights of the mind and heart. The feelings of love, yearning, grief, fear, and hope that saturated my writing were of a different dimension than I’d ever experienced. It was scary and uplifting and staggering and wondrous—sometimes all in the same moment.

Nancy:

Because I am not familiar with your nonfiction books, or know much about the topics you cover, would you like to elucidate? Perhaps how, like River, you deal with misunderstood “differences”?

Ellen:

When you write a book, much of the reading world wants to deem you an expert on your subject matter. I’m no expert on postpartum mental illness, and I was no expert on autism when I wrote my four books based on what I’d learned in raising my son, books that struck a chord and have remained popular through the years.

I believe that connection comes from my having been able to write about a complex and emotionally charged human condition in a timeless and accessible manner, removes the fear and champions hope.

For that, I’m constantly fending off the label of “expert” in a subject for which I have no formal training. So I’ve redefined the label, just as I did for the labels society tried to apply to Annie and my son. They do share the experience of being misunderstood, and often judged, for their neurological differences.

What I do well—my true “expertise”—is to tell a story from perspectives not commonly considered and tell it in a way moves people to shift old, ingrained perspectives, sometimes incrementally, sometimes seismically. It starts conversations. It builds healthier relationships and leads to constructive actions. It can be expansive and thrilling. It’s a privilege that never fails to humble me.

Nancy:

Annie finds great comfort in Emily Dickinson's poems. And of course, Thoreau is quoted. Are they some of Ellen's favorite writers? Dickinson touches on so many things in her poems, from the beauty of nature, to passion, to despair. What poems do you think were Annie's favorites?

Ellen:

I have always loved Thoreau, so that was a piece of myself that I injected into the book.

Dickinson, on the other hand, was not one of my favorite poets, quite the opposite, in fact. I have no idea why she became such an important thread in the story, or why the particular poems excerpted in the book, presumably Annie’s favorites, came to me. It was another one of those things that I heard with my third ear. I didn’t question it or let my own opinion intrude on it. I’ll never know, but perhaps it was a gift to me from Annie, because I certainly came to a far better understanding and appreciation of Dickinson and her work than I had before. Reading Aife Murray’s Maid as Muse: How Servants Changed Emily Dickinson’s Life and Language was both eye-opening and soul-opening.

Typical quilts of the early 19th c were pieced, formal, repetitive blocks placed side by side or separating by sashing. Below is a family heirloom quilt made by my husband's great-great-grandmother, typical of an early 20th c quilt.

Below is the popular Log Cabin block in a quilt top circa 1890-1915. The fabrics include mourning prints, indigo and cadet blues, a maroon diaper print, and madder brown. The light prints are shirtings in stripe and plaids.

But there were a few 'mavericks' who, using applique or inventive use of piecing, created something of their own. These were typically Pictorial Quilts, some of which have become quite famous in the quilt history world.I'd like to share some of these extraordinary quilts.

This 1853 Farm Scene quilt in the Museum of American Folk Art was made by Sarah Ann Garvis of Pennsylvania. Family history told that Sarah made it at the time of her engagement. The background is chrome orange. Photo from American Quilts, A Sample of Quilts and Their Story by Jennifer Regan, Gallery Books, 1989.

The Iowa Farm Quilt by Marianna Hoffmeister, made in 1880, blends her life with the Rev. Hoffmeister with memories of New Orleans where they met. Note the palm trees and the night sky. Photo from American Quilts, Regan. Quilt from the Hennepin County Historical Society.

Bill Volkening has an amazing collection of American quilts. One he acquired is the pieced Pictorial Quilt with American Flag, unknown maker, Ohio, cottons, c. 1930, dimensions: 64" x 75". Collection of Bill Volckening, Portland, Oregon.

See Bill's other quilts at his website The Vockening Collection.

In the 1970s, a revival of traditional quiltmaking was accompanied with artists discovering fiber as a new medium. Pictorial and original quilts became common.

My friend bought a contemporary pictorial quilt made in Caohagan in the Philippines. Read more about it here.

from the author's website:

An internationally renowned author, Ellen Notbohm has written award-winning books on autism and her articles and columns on such diverse subjects as history, genealogy, baseball, writing and community affairs have appeared in major publications. Ellen is an avid genealogist, knitter, beachcomber, and thrift store hound who has never knowingly walked by a used bookstore without going in and dropping coin.Set a hundred years ago and inspired by a mysterious ancestor in Ellen's family tree, The River by Starlight is the story of Annie whose postpartum psychosis ended her first marriage and separated her from her daughter. Her brother invites her to join him in Montana and Annie is eager for a new start.

She meets Adam who is drawn to her fiery strength and quick mind. They marry and settle down to farm, at first prospering but later hit by climate change. Mental health issues follow a series of losses, including miscarriages and the death of a child, resulting in Annie's institutionalization. Yet Annie rises again to cobble together a meaningful life.

The book is a wonderful read, with sympathetic, conflicted. characters, snappy dialogue, and a vivid Montana setting. Through Annie's life, the novel considers how women's health issues have been treated in a patriarchal society. (Read my full review here.)

Annie's love for Adam is represented by a marriage quilt she made for his eyes only. She creates an quilt that displays her independent mind and spirit. Because I am a quilter, I began by asking about the quilt.

Nancy:

The quilt Annie makes Adam is a symbol of their connection and shared life. Please talk about how the quilt came into the story.

Ellen:

This question goes right to the intersection between writing fiction and drawing from true story. You have lots of facts and lots of gaps. You have to listen for direction with your third ear, as I call it.

I don’t know how the quilt came into the story; it just did. Knowing so little about Annie when I decided to write her story, I read extensively about the places she lived and the times during which she lived in those places. Piecing that research together—like a quilt—with the insights and information I was gathering about her and Adam specifically, I began to construct their world.

The quilt grew out of that, and how it grew! It became a touchstone for so many things. A symbol of their intimacy, as Annie won’t let anyone other than Adam see the quilt. A stark representation of gender differences, as Annie and Adam view the quilt’s role in their lives differently, as it exerts a different kind of power over each of them. And ultimately, the quilt becomes a standard bearer for resilience and hope.

Annie’s quilt isn’t the only one in the book. We learn that as a young girl, Annie was dismayed by the traditional wedding quilt made for her sister by friends—the neutral colors and strict symmetry of the tree pattern defied what Annie already knew to be true of life’s uneven trajectory. Her own vibrant quilt would be her counterpoint to that.

|

| Crazy quilts and other quilt patterns Annie dismissed Quilts from Pentwater, Michigan residents |

Later in the book she encounters a very old quilt which also carries a message she needs to hear but almost misses. We also learn that she made her brother a quilt, “no-nonsense patchwork of duck cloth, corduroy, and denim” heavy enough to “keep her in her place” when she uses it.

Nancy:

There are detailed descriptions of the fabrics Annie chooses which are correct to their time, and not all novelists who include quilts in their stories are aware of fabric and quilt history. Is Annie's quilt based on any historic quilts you have seen? Did you research quilting in the early 1900s?

Ellen:

Yes. The fabrics and colors described are authentic to the day. The traditional patterns Annie rejected—Log Cabin, Bear Paw, Wedding Ring, Crazy Quilt—were also authentic to the period. Annie’s quilt, The River by Starlight, is free-form, which didn’t become popular until much later, perhaps the 1970s.

She also broke with tradition in buying all new fabric for her quilt. In her time and economic class, quilts were most often pieced from fabric scraps of previous projects—dresses, shirts, curtains, etc. In a passage that, alas, was lost to the editing process,

Annie makes a “decadent” decision:

“She remembers a blouse she made for church in Iowa, in the bottom drawer, never worn. Yellow with tiny wheat sprigs, ideal for the moon. But no, she decides, and taps a bolt of blazing chrome orange. No castoffs, no tailor samples, no dress scraps for this quilt. This will be a quilt without any ties to any past. All new fabric, it’s a decadent splurge, but for what better purpose?”

I thoroughly enjoyed the book Border to Border: Historic Quilts and Quiltmakers of Montana by Annie Hanshew. It didn’t influence my writing about my Annie’s quilt, as I was already several years deep into the writing about it. But the cover of the book did inspire me to write a scene wherein, at the end of her life, Annie makes a quilt for her daughter as a wedding gift. That one too fell to the editor’s knife, alas. But it lives on in my heart, so who knows where it might show up?

Nancy:

I read that you are a genealogist and that the novel is based on a true story. I would love to know about the inspiration story and how you decided to write about it. Did the actual people 'come to life' in your mind's eye?

Ellen:

Genealogists are familiar with the “brick wall.” Every family has one—the person that no one will talk about. There’s usually an aura of disgrace or taboo hanging around that silence.

Annie was the person behind the brick wall in my family tree. I saw her as a woman and a mother and a person whose blood runs in the veins of my children, and I felt compelled to know her story. I had only one little crumb of information to go on, but I sent that crumb on countless goose chases until I finally broke through the brick wall.

The root of those generations of zipped lips—perinatal and postpartum mental illness in an age of extreme gender disparity and social stigma born of ignorance. It demanded that I tell Annie’s story. The actual people did come vividly to life, not so much in my mind’s eye as in my heart.

Nancy:

I also do genealogy and spent ten years researching a 1919 diary and have more pages of research than diary pages! I have wondered how to present the woman behind the diary. So I am interested in knowing more about your handling of the historical records that became your novel. How do you transform the “cold facts” found on a census or death certificate into a narrative or character?

Ellen:

The common thread in all historical records is that they were recorded by people, and in every era, people have been influenced in their thoughts and actions by the conditions of the moment and of the times in which they live.

The “cold facts” found on censuses or death certificate are frequently not as immutable as we may think—information is only as good as the person who gave it and the person who recorded it, and human fallibility is itself a cold fact. The person giving the information may not have the correct info, and the person recording it may be in a hurry, not feeling well, indifferent to accuracy, distracted by any the things that can distract us on the job.

In the case of older censuses, it wasn’t uncommon for family members or even neighbors to give information about individuals who weren’t at home when the census taker came around. That’s why you’ll find that census info on the same person over several decades of will show a variety of birthdates, birthplaces, spellings of names, immigration dates. Death certificates are also open to bias and error. The informant on a death certificate could be anyone from a close relative who either did or didn’t know the deceased well (children often didn’t know their parents’ origins), to a harried hospital or nursing home staffer who guessed at info or recorded hearsay. Records often contradict one another, so which one is the “cold fact”?

Historical documents are starting points, to which we must always search for context. It’s the context of the events of a life and how it shaped that person, not mere facts, that make a compelling story.

Of course, it’s nigh impossible to reconstruct the context of every event of an entire life. That’s where the author must decide where on the literary spectrum to take the story. I originally conceived Annie’s story as creative nonfiction. But the gaps and contradictions in the historical records shimmered with mirage-like questions of why? and how? Unexpectedly, fiction became the format through which I could best explore those questions and tell her tale.

Nancy:

Your previous books were nonfiction. The River by Starlight has beautiful writing and delves into intense emotions. What were the challenges and joys of working in fiction?

Ellen:

My nonfiction writing wasn’t without deep emotion and engaging writing, so it was a kind of training ground, especially my history articles for Ancestry magazine, many of which sprang from my research for The River by Starlight.

An editor once groused, “I hate the fact that you hook me all the damn time with your heart-wrenching stuff.” The challenge for me in writing fiction about real people was, am I portraying the message they would have wanted? How do I reconcile that, in the name of literary license, some collateral characters based only loosely on real people may be nothing like those real people, for better or worse?

The joy came from venturing to places previously unimagined, whether in my six research trips across Montana, North Dakota and Alberta, or in the vivid places I went in flights of the mind and heart. The feelings of love, yearning, grief, fear, and hope that saturated my writing were of a different dimension than I’d ever experienced. It was scary and uplifting and staggering and wondrous—sometimes all in the same moment.

Nancy:

Because I am not familiar with your nonfiction books, or know much about the topics you cover, would you like to elucidate? Perhaps how, like River, you deal with misunderstood “differences”?

Ellen:

When you write a book, much of the reading world wants to deem you an expert on your subject matter. I’m no expert on postpartum mental illness, and I was no expert on autism when I wrote my four books based on what I’d learned in raising my son, books that struck a chord and have remained popular through the years.

I believe that connection comes from my having been able to write about a complex and emotionally charged human condition in a timeless and accessible manner, removes the fear and champions hope.

For that, I’m constantly fending off the label of “expert” in a subject for which I have no formal training. So I’ve redefined the label, just as I did for the labels society tried to apply to Annie and my son. They do share the experience of being misunderstood, and often judged, for their neurological differences.

What I do well—my true “expertise”—is to tell a story from perspectives not commonly considered and tell it in a way moves people to shift old, ingrained perspectives, sometimes incrementally, sometimes seismically. It starts conversations. It builds healthier relationships and leads to constructive actions. It can be expansive and thrilling. It’s a privilege that never fails to humble me.

Nancy:

Annie finds great comfort in Emily Dickinson's poems. And of course, Thoreau is quoted. Are they some of Ellen's favorite writers? Dickinson touches on so many things in her poems, from the beauty of nature, to passion, to despair. What poems do you think were Annie's favorites?

Ellen:

I have always loved Thoreau, so that was a piece of myself that I injected into the book.

Dickinson, on the other hand, was not one of my favorite poets, quite the opposite, in fact. I have no idea why she became such an important thread in the story, or why the particular poems excerpted in the book, presumably Annie’s favorites, came to me. It was another one of those things that I heard with my third ear. I didn’t question it or let my own opinion intrude on it. I’ll never know, but perhaps it was a gift to me from Annie, because I certainly came to a far better understanding and appreciation of Dickinson and her work than I had before. Reading Aife Murray’s Maid as Muse: How Servants Changed Emily Dickinson’s Life and Language was both eye-opening and soul-opening.

*****

At the time when Annie made her wedding quilt most quilters used traditional quilt block patterns. Crazy quilts had dominated the late 19th c but were on the wan by WWI.

Quiltmaking In the Early 20th c. and Pictorial Quilts

Typical quilts of the early 19th c were pieced, formal, repetitive blocks placed side by side or separating by sashing. Below is a family heirloom quilt made by my husband's great-great-grandmother, typical of an early 20th c quilt.

|

| Single Wedding Ring quilt, circa 1915, made by Harriet Scoville Nelson Turkey red and white, machine sewn, tied. |

|

| circa 1900 Log Cabin quilt top |

This 1853 Farm Scene quilt in the Museum of American Folk Art was made by Sarah Ann Garvis of Pennsylvania. Family history told that Sarah made it at the time of her engagement. The background is chrome orange. Photo from American Quilts, A Sample of Quilts and Their Story by Jennifer Regan, Gallery Books, 1989.

|

| 1853 Farm Scene |

The Iowa Farm Quilt by Marianna Hoffmeister, made in 1880, blends her life with the Rev. Hoffmeister with memories of New Orleans where they met. Note the palm trees and the night sky. Photo from American Quilts, Regan. Quilt from the Hennepin County Historical Society.

|

| The Iowa Farm Quilt |

Bill Volkening has an amazing collection of American quilts. One he acquired is the pieced Pictorial Quilt with American Flag, unknown maker, Ohio, cottons, c. 1930, dimensions: 64" x 75". Collection of Bill Volckening, Portland, Oregon.

|

| Pictorial Quilt with American Flag |

In the 1970s, a revival of traditional quiltmaking was accompanied with artists discovering fiber as a new medium. Pictorial and original quilts became common.

My friend bought a contemporary pictorial quilt made in Caohagan in the Philippines. Read more about it here.

Sunday, May 6, 2018

The River by Starlight: A Story of A Woman's Hope and Resilience

"The evening star, multiplied by undulating water, like bright sparks of fire continually ascending." The River by Starlight, from the Journal of Henry David Thoreau, June 15, 1852

Annie made the quilt for her future husband, for his eyes only.

There was a block with a sliver of chrome orange moon and a fabric with a chrome yellow shower of stars. The twilight sky was represented with a dark sapphire with a swirl of white dots and a cadet blue shot with white. At the bottom curved a river in green fabric. She called it River By Starlight.

In 1911 Annie Rushton had received a letter from her older brother Cal, inviting her to come to Montana where he had settled. At age 26, Annie was living with her mother after postpartum psychosis destroyed her marriage and separated her from her baby daughter.

Annie hopes that Montana will bring the freedom she craves and the new beginning she desperately needs. Annie travels light, only taking her ivory knitting needles, her Emily Dickinson inscribed "with everlasting love" by her ex-husband, and her grandmother's rose glass jar.

She never expected that Montana would bring a man who would claim her, body and soul, or imagine the ecstasy and the crippling pain and loss their love would endure, driving Annie to a desperate choice.

Ellen Notbohm's novel The River by Starlight is based on true events which she spent years researching. Notbohm wanted to give voice to the women, who a hundred years ago and with few resources, suffered mental health issues in a male-dominated health and justice system.

Annie is an amazing character, strong and feisty, quick-witted and quick-tempered. I loved the dialogue between the characters. Although Annie suffers many losses, she also is resilient and a survivor. The misunderstandings between men and women and the compromises they make ring true. The writing is gorgeous.

Readers will be swept back in time and won't soon forget the vivid characters.

I received a free book through NetGalley in exchange for a fair and unbiased review.

The River by Starlight

by Ellen Notbohm

She Writes Press

Publication: May 8, 2018

$16.95

ISBN: 9781631523359

Learn more about the publisher, She Writes Press, at

https://shewritespress.com/about-swp/

Annie made the quilt for her future husband, for his eyes only.

There was a block with a sliver of chrome orange moon and a fabric with a chrome yellow shower of stars. The twilight sky was represented with a dark sapphire with a swirl of white dots and a cadet blue shot with white. At the bottom curved a river in green fabric. She called it River By Starlight.

In 1911 Annie Rushton had received a letter from her older brother Cal, inviting her to come to Montana where he had settled. At age 26, Annie was living with her mother after postpartum psychosis destroyed her marriage and separated her from her baby daughter.

Annie hopes that Montana will bring the freedom she craves and the new beginning she desperately needs. Annie travels light, only taking her ivory knitting needles, her Emily Dickinson inscribed "with everlasting love" by her ex-husband, and her grandmother's rose glass jar.

She never expected that Montana would bring a man who would claim her, body and soul, or imagine the ecstasy and the crippling pain and loss their love would endure, driving Annie to a desperate choice.

Ellen Notbohm's novel The River by Starlight is based on true events which she spent years researching. Notbohm wanted to give voice to the women, who a hundred years ago and with few resources, suffered mental health issues in a male-dominated health and justice system.

Annie is an amazing character, strong and feisty, quick-witted and quick-tempered. I loved the dialogue between the characters. Although Annie suffers many losses, she also is resilient and a survivor. The misunderstandings between men and women and the compromises they make ring true. The writing is gorgeous.

Readers will be swept back in time and won't soon forget the vivid characters.

I received a free book through NetGalley in exchange for a fair and unbiased review.

The River by Starlight

by Ellen Notbohm

She Writes Press

Publication: May 8, 2018

$16.95

ISBN: 9781631523359

Learn more about the publisher, She Writes Press, at

https://shewritespress.com/about-swp/

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)